Jo-Ha-Kyu & Story (Upd. Nov 12, ’22)

“Every phenomenon in the universe develops itself through a certain progression. Even the cry of a bird and the noise of an insect follow this progression. It is called Jo-Ha-Kyu.” – Motokiyo Zeami (AD 1363 – 1443)¹

Jo — a bowl and water that begins dripping or will drip

Ha — the water drips, gradually raising

Kyu — the water pours out from the rim

The soul of butoh is not really about form alone, but individual essence or story/plot, especially if pulled from the subconscious (shadowbody). Essentially, the Japanese words Jo-Ha-Kyu involve the three major parts of a story–beginning/opening (thesis), middle/development/thru-line (antithesis), and end/climax (synthesis).¹ For instance, in Tatsumi Hijikata’s Bugs Crawl, we begin with the simple awareness of the situation and a single bug (Jo), then bugs gradually infiltrate (Ha) till there is nothing left but bugs (Kyu), then there is a resurrection (Kyu/New Jo). Sometimes the line between Kyu and a New Jo may be difficult to see. Catharsis, for instance, may be viewed as the climax, but also a new beginning.

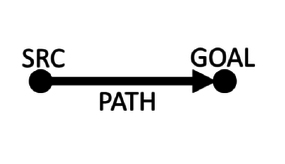

In terms of contemporary metaphor theory, Jo-Ha-Kyu fits the image schema of SOURCE-PATH-GOAL. Image schemas to Lakoff and Johnson are “recurrent patterns in perceptual-motor experience that derive from our bodily interaction with the physical world.” The source–path–goal schema is a very primordial schema and is related to human conceptualization itself/sense-making.7 Like so many other image schemas, we are bombarded with this schema at all moments of our lives.

In terms of contemporary metaphor theory, Jo-Ha-Kyu fits the image schema of SOURCE-PATH-GOAL. Image schemas to Lakoff and Johnson are “recurrent patterns in perceptual-motor experience that derive from our bodily interaction with the physical world.” The source–path–goal schema is a very primordial schema and is related to human conceptualization itself/sense-making.7 Like so many other image schemas, we are bombarded with this schema at all moments of our lives.

Jo is often small or slow due to serving as an instigation/novel phenomenon, even though it is also very large because it is the opening of an entire universe. Ha is quite often very involved and spans more time, and Kyu can also be small. Small, however, does not mean less intense, just a wrap-up. Because of this, it is not unheard of to hear of Jo-Ha-Ha-Ha-…Kyu.

There can be a Jo-Ha-Kyu within the entire span of a piece or there can be a Jo-Ha-Kyu within one qualia, one among several Jo-Ha-Kyus. There can be a Jo-Ha-Kyu in the throwing of a rock. All shadow work especially contains the Jo-Ha-Kyu, and the Kyu is sustainability/catharsis/healing.

For clarity’s sake, let’s take Joseph Campbell’s story circle (The Hero’s Journey) as fit into Dan Harmon’s categories as an example, and identify the Jo-Ha-Kyu.²

- You (a character is in a zone of comfort) (Jo)

- Need (but they want something) (Jo)

- Go (they enter an unfamiliar situation) (Ha 1)

- Search (adapt to it) (Ha 2)

- Find (find what they wanted) (Ha 3/Kyu)

- Take (pay its price) (Kyu)

- Return (and go back to where they started) (Kyu/New Jo)

- Change (now capable of change) (New Jo)

(As you can see, sometimes the placements of the Jo, Ha, and Kyus are up for interpretation. Not to mention there are meta-Jo-Ha-Kyus within each Jo, Ha, or Kyu.)

Exercise 1: Throwing Jo-Ha-Kyus

As a jumping wild exercise, one person throws out various Jo-Ha-Kyus one at a time (first Jo, then Ha, then Kyu). Examples: question, thesis, conclusion / inadequate, adequate, too much / sensation, action, result / birth, life, death.

Exercise 2: Throwing Jo-Ha-Kyu Variations (Intermediate)

This is a reduced/deterritorialized Jo-Ha-Kyu jumping wild exercise. One person can edit/remix the concept of Jo-Ha-Kyu and one at a time throw either Jo, Ha, or Kyu, but the order may shift. If for instance we throw a Jo followed by another Jo, then the story or scenery is constantly shifting and being felt. Or somebody may call out Jo then Ha, then decide Jo → Ha → Jo then Jo → Ha → Kyu → Jo followed by Jo → Kyu.

Exercise 3: Real Life Jo-Ha-Kyu

This is an exercise in noticing Jo-Ha-Kyus around us. Become a people-watcher (performance voyeur) and locate the Jo-Ha-Kyu within the scenery. For instance, in the Shadowbody YouTube series known as Butoh in Real Life, video #32 (Fence Man 2) shows a simplified Jo-Ha-Kyu world change process of a drunk man: (1) Not shown prior to the video, the man will have obviously shown the need to get out of the park (Jo); (2) He tries to go between the bars (Ha 1); (3) He tries to climb up and fails (Ha 2); (4) A new character enters who implies the actual exit (Ha 3); (5) He goes through that exit to his belongings (Kyu).

Jo as Conflict/Proflict

“Two dogs and one bone.” – Robert Peck

Something happens, a thesis, and this something provokes someone or something to do something. Here are five different types of conflict with examples taken from Tatsumi Hijikata’s butoh writing entitled Sick Dancing Princess, which were childhood memories.

1. Charater Versus Nature

Hijikata stated, “Often, I was about to be eaten by snow, and in the fall, by grasshoppers.”³

2. Character Versus Society/Culture

The princess in Sick Dancing Princess may be dedicated to Hijikata’s kidnapped sister. He mentions his sister under the title “My Sooty Princess.” According to Rhizome Lee, during the Second World War, the Japanese government kidnapped and made her a prostitute for the soldiers. This provoked unfinished business within Hijikata. He had questions. Why did his sister have to leave? Is she dead? Could he take vengeance? Hijikata had to resonate with this sick system did to his sister and him. He dressed in her garments, and did such in his last piece entitled Quiet House.³

3. Character Versus Character

Hijikata noted that he was caught looking at a woman inside a house trying on a kimono, and she looked at him with a “terrible face” and “tight eyes.” He then ran out the back door silently and began looking at a stick, and before he knew it, he had turned into the stick.4

4. Character Versus Self

Hijikata wrote, “The boy as me suddenly became stupid without any intention and kept like a strange brightness, and just barely alive. And yet, my eyes fell into something shady as if they were cursed. I had an excessive curiosity towards such nameless things as lead balls or string.”³

5. Character Versus Technology

Kyu as Peacock or Surprise

Another interpretation of kyu is quick which does not necessarily have to relate to the speed. Using the metaphor of the water bowl, the kyu is the finale and can often be associated with peacock or surprise. What is the juicy ending that has to happen with tame or perfecting timing?

Tatsumi Hijikata used the term peacock as a big surprise as he recounted a story of encountering a peacock at his friend Mr. Yanagida’s yard.11

Very rewarding is when multiple peacocks follow each other not unlike being hit by a punchline, only to get yet another one after unexpectedly.

Jo-Ha-Kyu as Birth to Death

Birth is an instant universal phenomenon, and birth is even a conceptual metaphor for creation in Lakoff’s list of conceptual metaphors.”8

If Jo is birth, Kyu can be death. The Kyu if seen as a serious matter as death brings to mind Artaud’s realm of the cruel and essential theatre where something immediate or bloody real finally happens, a “hungering after life, cosmic strictness, relentless necessity, […] a living vortex engulfing darkness, […] a necessary pain without which life could not continue.”9, 10

One is always finding the ending, which has to be the best ending possible, the only chance one has, the last dying wish. The freshest peacock.

The Ha(s) can be that which is between life and death, which is the journey of life, and it may be a laughable thing, ha-ha.

Myth & Primitive Narrative

To Geoffrey Galt Harpham (of On The Grotesque), myth is a form of primitive narrative, but is all the more liberated. He mentions, “What distinguishes the primitive narrative is a tendency to treat everything–even the gods, even the dead–as palpable and living presence.”6 Like with animism, everything is alive, so there are endless qualias to resonate with. The usual notion of logic then takes a back seat.

Harphan continues, “Myth is the infancy of narrative, and inhabits more advanced ways of knowing as our own infancies inhabit us. Speaking of . . . sacred time of the Beginnings, before history and profane time, it offers . . . a release from the tensions and alienations of abstraction, healing the self divorced from the raw material of life and providing a tonic affirmation of the wholeness of existence.”6 Hapharm here is speaking of none other than the subbody and how incorporating it into one’s life can be a means of reaching Kyu/New Jo catharsis/therapy/integration/synthesis.

Momiyose

Momiyose is a form of Jo-Ha-Kyu where the Kyu is a condensed culmination of the Jo and Ha. For instance, if it takes a minute or two to open and feel the Jo scenery/qualia, and another 8 to travel the journey of changes (Ha-Ha-Ha), then perhaps one chooses a 1 minute climax merging together (whether linearly or not), everything that occurred within the Jo and Ha.5

Several encounters of near-death experiences have the life review or life flashing before one’s eyes. This is very much like a Momiyose Kyu.